So, I wrote a book. Actually, I wrote three books. Or four, but who’s counting? People always ask me “How do you write a book?” The fact is, I don’t know. I only know how I wrote a book. And how I wrote a book is a lot like how I had three boys in three years: I loved it, but I don’t recommend it.

I’ve read enough of the millions of writing websites/forums/social media posts to know that every writer’s process is different, so I can only tell you mine.

Mine began with a dream.

Believe You Are a Writer

When I was a little girl, I dreamed of writing a book. I would sit with paper and pencil on the shady back porch of my childhood home and create characters and imagine their stories. Writing was my favorite thing, and I even sent a poem to a children’s magazine called Highlights about snow. My poem rhymed perfectly, and it envisioned something I had never seen growing up in southern Texas. With this poem, I learned my first thing about publishing: it takes a long time. By the time it appeared in the magazine, several years had passed and I felt too old to claim such a childish sonnet. No one knew I was a writer, except me.

In my teens and young adulthood, I still saw myself as a writer. I wrote essays for my friends at school, and I wrote for the high school newspaper. My letters to friends were long and descriptive. I wrote legal documents as a paralegal and vivid portrayals of victims and their families to ensure justice. I wrote a well-received Christmas musical for my church about a crotchety old man who invites his family home after years of estrangement. People told me they enjoyed receiving my Christmas letters telling the story of our family each year. I began writing a complex murder mystery set in the hill country of Texas, about two women born in different worlds and eras, each holding missing pieces of a puzzle they could only solve together.

And then I forgot I was a writer.

Life was busy. I mothered my three boys and assisted my aging parents. My sons began heading off to college, and a tiny seed of writing desire implanted itself in the back of my mind, but I buried it under a thick soil of rationalization that it was a silly idea whose time had passed. Then my dad died, and my mom moved to a memory-care facility a few miles away where I helped care for her. It was a hard time, and I needed an escape, so I began imagining stories again, like when I was young, with a keyboard and screen instead of pencil and paper. Then, my mom died, and my grief and my dream were no longer insulated by busyness, and there were no more excuses. So, I wrote.

A Novel Begins with a Story

I never knew my grandfather, who died when my mother was twelve years old. He immigrated alone after the First World War from Germany to America through Mexico, and my mother lost touch with his family in Germany after her father died. My German American grandfather had Jewish friends, and as a young girl, my mother understood he did not like Adolf Hitler, but I often wondered about his family back in Germany who lived in the bullseye of World War II. Were they Nazis? Did they cheer for Hitler? What was it like to live through the rise of the Third Reich? How did this happen? What would I have done? Would I have been on the right or wrong side of history? A story sparked.

Years later, a forgotten stack of letters fanned the latent ember to flame. I found them under my parents’ bed when they downsized, and I discovered they were from my grandfather’s sister Paula and her twenty-something daughter Edith—my great aunt and first cousin once removed. There were thirty numbered letters, dated 1947-1948, with crisp German cursive on wafer-thin paper. They didn’t tell me whether my aunt and cousin were Nazis, but I learned that, like many Germans, they were starving after the war. The letters thanked my grandfather for saving their lives by sending food and supplies. They seemed like normal, nice people who loved receiving my mother’s crayon drawings. One of my mom’s earliest memories was standing in line holding her father’s hand at the post office to mail a care package to these mysterious relatives she would never meet. Last year, I met Edith’s son, and the circle was finally complete. And yet still incomplete. No one talked about the war. I will never know what my relatives thought or experienced.

I needed to learn more.

Research

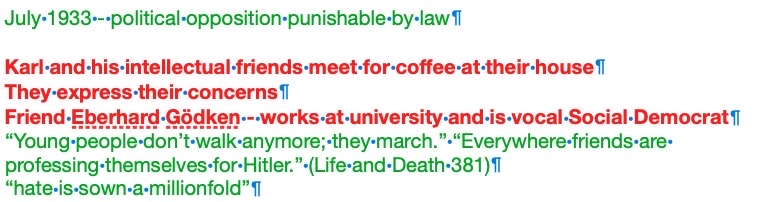

All writers must do research in order to provide depth and accuracy to their stories. Murder mystery writers worry about someone perusing their search histories with concern, finding topics such as how long it takes someone to die from bleach poisoning. Mine is full of Nazis and Hitler and death camps. At one point, my boys asked me to put away my “swastika books” when company came over. I immersed myself in Germany’s history and perspective, knowing I would have to erase hindsight and my American hubris to fully understand the story.

I read many books and burrowed down into a Google black hole, compiling a database of over a thousand links to pertinent information. It was hard to find the primary sources I craved, as survivors worked hard to whitewash the past and very few readily admitted to supporting the National Socialists. I didn’t want to know about the avid supporters or open resisters. I wanted to understand the gray people in the middle who remained silent.

Give Birth to Characters

As I learned about the German people and read first-hand accounts, characters emerged in my head. A woman born at the turn of the century who loses two brothers in the Weltkrieg, or world war. Her wealthy, intellectual husband. A sister who struggles through the turbulent 20s. Her father, whose factory can’t make money and who feels the fledgling Weimar Republic doesn’t care about the ailing middle class. A brother, who never got to fight in the world war and is looking for someone to blame for his own economic troubles. Her ex-fiancé, who is looking for identity and finds it in a Nazi uniform.

As I fleshed them out in my mind, they demanded to be named, so I spent weeks poring over names and choosing them like an expectant mother. Elisabeth, who everyone calls Lili. Her sister Silke, whose full name is Cäcilie Maria. (Yes, everyone has a middle name or two.) Surnames were especially fun as the secret or essence of a character can hide in a German last name. I have a full family tree of characters, many of whom didn’t even make the book. I can tell you Lili’s first cousin’s name and when she died.

I dreamed about my characters and what they might say or do. In the foggy streets of my sleeping psyche, where settings were born from photographs I found online, I could talk to them and discover more about them. I set the story near the industrial heartland of Germany where my family lived, because after all, that is where it all began in my mind.

I had a cast of characters living rent-free in my head. Now what?

Outline the Story

In the world of fiction, there are two types of writers: "planners" and “pantsers.” I’ve never been one to fly by the seat of my pants. I'm not that gal. I’m a planner and boy, did I plan. The original outline of the story is over one hundred pages, and includes links to research, historical dates, plot points, and character reactions. It was important to me to ground every character in a real person I discovered in my research, and the story is based on actual events, which must stay anchored in time. The Munich Putsch and the treason trial of Hitler and the death of Hindenburg and the day the Nazis mandated yellow stars for Jewish people cannot move, and they form the backbone of the story like stops on an old AAA TripTik or modern-day Google Maps.

Combined with research and interrupted by the death of each of my parents, the pandemic, and major surgery, I outlined for several years, and the story took shape. I had characters based on real people woven through historical references and dates. I had a story to tell.

Write the Story

One of the hardest steps for a writer is getting those first words on the page. A blank page is a brutal bully, and a blinking cursor can feel like a waving sword threatening to kill all your hopes and dreams. But writers must write. And so I did.

There is a reason it is called a “rough” draft. I needed to learn how to write, and I scoured the internet for tips, used editing tools, and forced myself to write something every day. Some days were amazing, and words flowed off my fingertips. Other days, time ticked by, and no words appeared. That is still true today. Either way, I discovered I loved writing, and it had the same effect on my mood as reading a book or drinking a glass of wine. If I was having a bad day, my husband asked if I wanted to go write for a little while, with a knowing nod of his head.

I wrote 100,000 words of Lili’s childhood, covering her birth in 1900, her baby sister and brother, her older brothers, her summers and holidays in the wine country, and more. I wrote about all the things that shape her into the young woman she becomes.

And then I shelved it and started over.

Lili’s story was becoming War and Peace in the literal, 1400 pages kind of way. At this pace, the first 400 pages would only get Lili to her teens. I needed to begin the story later. I told myself nothing is wasted; nothing is lost. (Well, I’ve lost these first 100,000 words somewhere in the bowels of a hard drive, so let’s stick with nothing is wasted.)

I picked the story up in 1923, when Hitler, Lili, and her infant son all survive the Munich Putsch against all odds. Lili is a twenty-three-year-old wife and mother, and remembers her childhood through excerpts from my original writing. Nothing is wasted; some things aren’t lost.

Day by day, keystroke by keystroke, Lili’s story unfolded. Pages became chapters, and chapters became “Truths and Roses” which covers the turbulent period between 1923 and 1933 when the Nazis rise to power.

Revise, Edit, and Repeat

Like a frog ribbiting through the night, revising and editing never ceases. Stories must be fine-tuned for substance and word count. Beloved characters don’t make the cut—we writers call it “killing our darlings.” Buh-bye to Lili’s long-lost brother-in-law, Joachim, and her cousin Suze. RIP. I cut pages and pages of writing, including a breakfast argument I swore would win me a Pulitzer when I wrote it, because it didn’t advance the plot or provide new information.

I edit constantly as I write, and at the end of any day I swear that what I’ve written is perfect. It never is. It never will be. I loved diagramming sentences in high school and used to think of myself as a grammar nerd. Now it feels like hitting a golf ball into the rough daily and hacking through weeds to find it. Grammar is more subjective than you think in fiction, and even computerized software tools often disagree, leaving writers to ruminate on Oxford commas and hyphenated adjectives in our sleep.

When writers arrive at a point where we believe our book is perfect (it’s not), we attempt to complete the most death-defying act of all: publish it.

Publish It

In the age of Amazon, self-publishing has become a writer’s best friend or worst enemy, but neither this route nor the traditional publishing route is risk-free. Self-publishing puts the “self” in publishing, leaving the writer on their own to edit, market and sell their book, not to mention cover the costs of printing. In traditional publishing, one may have to die to self to suit the publisher’s wishes and get their book in the hands of readers. In the middle is the shark-laden sea of hybrid publishers. Whichever way, the goal and the main reason to write a book is for people to read it.

I have pushed my chips all in seeking a traditional publisher, which means I’ve just begun the soul-crushing process of finding a literary agent to sell my book to a publisher. Here’s how it works: you send a carefully crafted one-page query letter cleverly pitching your hook, book and cook. The “hook” is your short, catchy elevator pitch that makes someone want to read your book. The “book” gives the gist of the story without giving too much away. The “cook” outlines your writing experience and/or something interesting about yourself, i.e., “I have two heads!” Hundreds of hopeful query letters land in literary agents’ inboxes each day, along with a requested writing sample from the book that normally varies from five pages to fifty.

Writers choose which agents to query based on often esoteric wish lists they post on their websites. “Clara is seeking literary upmarket women’s fiction for men with speculative elements and strong but frail protagonists. She is especially interested in dark, twisted serial-killer stories that are light and uplifting.”

Some days, querying feels like an exercise of confidence and empowerment and I am convinced any agent will love my query letter and ask to read my book. Other days, it feels like death. Silence is rejection in the literary world, and silence is painful. Google tells me I have a 1 in 6,000 chance of landing a literary agent. Darn that Google.

Keep Writing

While I wait for an agent to recognize the brilliance of my writing and beg to see more, I am editing my next book. Living in the pages of a story I am writing brings me joy.

I persist because I am a writer, and writers write books they want people to read. Some writers become published authors, which is every writer’s dream. Some authors write best-sellers that we devour in our free time to remind ourselves why stories matter, and why writers write.

A friend asked me recently what I thought "little Amy" would think if I told her I wrote a book. I realized my young self would wonder why it took so long, because she knew I was a writer. I forgot for a while.

How inspiring! Like you, I've always been "a writer" - of elementary poems, high school essays, and oh how I loved college research papers! LOL I've never delved as deeply as you have - but wow, now I want to!! Best wishes on getting published - can't wait to read your book(s).

Wow, Amy! I love your writing and I cannot wait to read your books! Your writings are so significant and yet you insert such light and full circle come backs! I believe that "Young Amy" would say, "You were born to write!"

Cathy B.

I love this inside view of you and your writing!

This is a great article Amy. Wow, Highlights...very impressed, I loved that magazine. I have faith in you and have no doubt that "little Amy" would say "of course I published many books, it is my gift".

Love it!